This has been in the offing for a while, but now, it seems, it's out of the offing, and into the, er, inning. So: it's a very-near near-future-set thriller, written in Donald E Westlake/Richard Stark mode, about a man who steals spaceships for a living. Publisher: NeoText. Presently it's e-book only (not sure what may come, format-wise, in the future). On the upside, at the moment it's only 99c in the States, or 87p if you live in the United Kingdom. What have you got to lose?

Friday 18 November 2022

Wednesday 2 November 2022

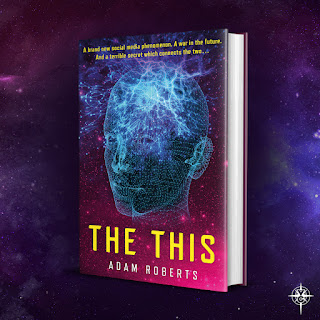

THE THIS: Mass-Market Paperback. Out Now!

The paperback edition of The This is set for release in a few days (10th November in fact) (10th Nov Update: 10th November is today! Now available to buy!). To mark that, here's the review the latest edition of SFX carries about the book: click to embiggen and clarify the image. 5 stars! Pick of the paperbacks! A little frustrating at the start! Will change your entire worldview if you make it to the end!

Wednesday 12 October 2022

From Birth to Now

I looked-up this 1850 map (for something Victorian-set I'm presently writing, in order to check the exact path of the Great Western Railway) and was struck by the compass of this small section of it. So: in 1965 I was born, in Mayday Hospital, now called Croydon Hospital: in the bottom right hand portion of this image. I grew up in Peckham, and then Sydenham. I presently live, as it happens, exactly where the folds in this map make a cross, north-west of Sunninghill and south-east of Wokingham. For portions of my life I have left this zone: as an undergraduate in Aberdeen and a graduate student at Cambridge, and after that for some years living in Southampton. But here I am again, in the middle of these arbitary crosshairs. Kismet, perhaps.

In a post on my Medium blog I meditated (in, surprisingly enough, given the topic, a rather NSFW manner) on the continuity of the Thames to my life. Where we currently live is a few miles from that great father river, but that's not say I don't continue to feel its influence. So here we are.

Tuesday 27 September 2022

Myth and Science Fiction

Coming up, this Thursday: ‘The Mythology of the Future’—a panel with myself, Beth Singler, Yen Ooi and Jennifer Woodward, part of the Science Fiction Squared Symposium, exploring the future of science fiction [Tickets still available, I think: Thu 29 Sep 2022,Island Social, Globe House, 34 Botanic Square, E14 0LU]. The brief for our panel is: ‘Mythology seeks to explain the unknown past; science fiction to explore the unknowable future. How do the forms of mythology relate to those of science fiction, and how are they received by their audiences?’ I’m looking forward to it. Come along, why don’t you?

I’m chairing the panel and don’t want to hog discussion, so I’ll note a few things here, and then will look to sit back and listen to what my excellent, expert fellow panellists have to say.

So, let's start with: what do we mean by ‘myth’? Well, that’s a large question, much debated. I suppose most people have a sense of myths as bodies of stories, of legendary fables—as it might be, the Greek Myths, the myths of King Arthur, perhaps (although Biblical literalists might object to this) the myths of the Old and New Testaments —sets of stories distinct from, though not necessarily entirely alien to, ‘actual’ history. That is to say, we think of myths as departing from certain canons of truthfulness, verisimilitude, historical accuracy and so on, but nonetheless as articulating other kinds of truth. There may or may not have been a historical Arthur (I used to believe there was when I was a teenager; now I tend to doubt it) but, if there was, his life and times were certainly very different from the body of myth that has accrued around his name. But though those myths won’t accurately represent Dark Age Britain, or the political and martial life of a post-Roman dux bellorum, that’s not to say that they’re lies. They capture, we could say, a different kind of truth, speaking to us about core human concerns: about courage and leadership, about persistence and fidelity and doing-the-right-thing, about the place of individual love in the context of social and traditional rigidities, and—with the Sangraal episodes—about sanctity, about faith and renewal.

There have been plenty of theorists of myth. Freud, for example, thought myths existed to articulate, and therefore address and purge, psychological anxieties, traumas and taboos—so, for instance, the myth of Oedipus, inadvertently sleeping with his mother and afterwards pulling out his own eyes, is (Freud says) actually ‘about’ castration anxiety, something bound-up in the Freudian primal scene of love for mother and (castrating) hostility to father. This approach treats myths as symbolic articulations. It hasn’t, we can say, found many supporters among classical scholars and students of Greek myth. Robert Graves for instance points-out that the Greeks had no problem including actual castration in their myths, which makes this kind of evasive symbolism superfluous.

There are plenty of other theories, but I’m going to zero in on one in particular, because I’m interested in what it might tell us about the coming-to-prominence of SF stories as modern myths. I'm doing so because, it seems to me, a set of science fiction tales, or megatexts, does indeed function today as modern myth, in the sense that we all have these texts and stories in common, we all recognise references from and allusions to them, they are stories not true in the strict sense—they’re science fiction, after all—but which still speak to people, which embody and articulate metaphorical and deeper truths. Star Wars is, I suppose, the most obvious example: one modestly-budgeted 1977 film made from a B-movie pastiche script that has, amazingly, proliferated to dozens and dozens of (often very high budget) sequels, prequels, spin-offs, paratexts and merchandise. Star Wars permeates modern culture and we might argue it does so because it functions as a myth. I don’t mean that it is the latest livery in which Joseph Campbell’s ‘Hero With A Thousand Faces’ gubbins gets itself dressed. Lucas certainly read Campbell before he wrote his initial script, but Campbell’s book is a piece of vapid synthesis that, by amalgamating a variety of different stories to one sub-Jungian archetype, misses the specificity and valence of actual myths from which their potency derives.

Star Wars not a myth about sex, I think (there are lots of myths about sex, but this isn’t one) which is why the franchise feels so juvenile and limited on that front. Nor is the core myth about, as it might be, diversity, acceptance, identity and so on—those things are very important, and I don’t invoke them to snark, but I don’t think that’s at the heart of Star Wars as a myth. By all means cast diverse actors for these films (why the hell wouldn’t you?), of course ensure that diverse worlds and plots are part of the story. But the reason this B-movie went from Harrison’s Ford’s ‘George, you can type this shit, but you can't say it’ to world-spanning success was that it spoke to people in mythic terms. And, to repeat myself, I think the twinned linked myths of Star Wars are about individuality versus the dehumanising authority of society, and perhaps reality as such—and about the place of the spiritual and transcendent in an increasingly mechanised, tech-saturated, materialist world.

At any rate, Lévi-Strauss is an interesting way of framing all this, I think. I’ll be honest, I’ve come back to Lévi-Strauss. When I was a callow undergrad and into my postgrad years in the later 1980s, the cool beans all belonged to Deconstructionists, who were all about unpicking the Lévi-Strauss binarisms and structuralisms. Not that I’ve turned my back on this, but I now wonder if there’s more to the structuralist whassup than I used to think. Anyhow.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, famously, worked through the implications of structural linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure, parsing human being-in-the-world through a set of binaries. Human minds, says L-S, are complex machines, and the minds thus structured parse the larger aggregations of human societies. Myths, dit Claude, are ways in which we, collectively, and as individuals, mediate the polarising contradictions of existence as such. These opposites reflect the contradictions which we encounter in our lives. The ones Lévi-Strauss specifies are: desire and reality; individual and society; the possible and the impossible; nature and culture. Mediating these binaries is, says L-S, is in a sense the point of myth.

Now, you may be more or less persuaded by this perspective. But I wonder whether—let’s say—Star Wars doesn’t articulate precisely this: the franchise mythically mediating the binaries of individual-versus-collective (which is to say, individual-versus-everything) and materialism-versus-spiritualism. As to whether ‘myth’ is the, shall we say, ‘best’ way of doing this, or whether these myths speak to many people, that's a matter for debate. As we shall do this Thursday!

Friday 2 September 2022

The Big Read on “The This”: I Am Read, Bigly

Those excellent readers, Bill and Joel, are joined by ‘one of the best essayists in America’ (the TLS's words, not mine; though I agree with them) Phil Christman, to talk about my The This, which is about hive minds, social media, Coleridge and, most importantly, GWF Hegel. It is, I can be straight with you, amazing to me. Listen and see, or hear, for yourself. I mean, amazing. Amazing!

I'll be honest: it took me several goes to listen to this. It starts with some healthy American praise, which of course made me pull a face like I was sucking a whole lemon, to the degree that I had to stop listening, more than once. What's the matter with these geezers? Can't they call me a cunt, even once, to put me at my ease? But eventually I was able to listen to it all. Some very perceptive and interesting things, here! I am, as the discussion suggests, a big KSR fan. I also liked the idea that Alan Jacobs, Francis Spufford (the patron saint of the podcast, it seems) and I end up ‘not quite constituting an ism’, which I think is right. I am very pleased to call Alan and Francis friends, but the three of us have in the past noted that there's a off-kilter tripod-solidity to our affinity: Francis and I are Brits where Alan is American; Francis and Alan are Christians where I'm not; Alan and I are football fans and Fancis isn't. It makes for, I think, a thoroughly robust friendship logic. But Francis and Alan are both amazing, eloquent and penetrating writers and I'm honoured to be bracketed in their company.

Friday 5 August 2022

Strange Horizons Reviews "The This"; and Other News

Prashanth Gopalan finds The This to be ‘a wildly imaginative novel, a thought experiment on morality and social organization, and a meditation on time and consciousness.’

With its interesting theories about the roots of human social behaviour, organization, and culture, and its intense explorations of life within a hivemind, The This explores the nature of being and belonging, and what people might be willing to do to find belonging when they reach the limits of social atomization, language, and technology-based connection. This is an intricately constructed science fiction novel deserving of wider readership. I found myself constantly marveling at what Roberts was doing as I made my way through it. Judging by the plots of his other books, Roberts is an exciting and underrated author, whose works featuring picaresque protagonists, grand themes, and erudite philosophical explorations may help us navigate the complex moral choices we face at a time when our future as a species feels increasingly uncertain—and unearth startling, if unsettling, visions for how we could reimagine ourselves as a society for the sake of our survivalIt’s pleasing to get such a positive review, though I lay my finger on a couple of words in that paragraph—‘underrated’ and ‘deserving of wider readership’—and find within myself the capacity for gloom. But that’s just me. Twenty three novels into a novelist’s career if he or she is not rated and are lacking a wider readership, they probably won’t be and won't pick up one. That’s fine: there’s plenty of brilliant, widely-read and highly esteemed SF being published at the moment, which is the important thing.

Wednesday 13 July 2022

Latest News

I was asked yesterday about my blogs, and it occurred to me that I don't anywhere have them itemised or indexed. So here goes.

One. This blog, Morphosis, is now my stand-in author website. I used to run a site called adamroberts.com to that end, but it cost a surprisingly large amount of money and nobody ever visited it so I stopped my subscription and instead repurposed this Blogger platform as author website. Once upon a time it used to be a blog for critical thinking and essays and whatnot, and if you go back in the timeline you'll find all those posts, but now I use it for ... well: for this kind of thing. Author news, links to reviews and so on. Here's news of a recent review of my new novel The This, for example.

Two. I started a Medium blog, ‘Adam’s Notebook’, to host my critical essays, readthroughs of the complete works of Walter Scott, and other bits and pieces of writing. I can't say I'm overly enamoured of Medium as a platform (it's almost impossible to format posts beyond the Medium vanilla settings, its internal search and archive protocols are crap, it's glitchy and odd about updates, revisions to posted posts, timetabling posts ahead of time and so on) but I've been there for a while now. If you were interested and prepared to follow me I might reach the threshold where I could start to monetize my Notebook writing, but no pressure. At the moment, in addition to the Walter Scott, I'm posting thoughts pursuant to a short history of Fantasy that I'm working on (for example: why are so many Fantasy novels published as trilogies?), with some reviews, occasional poems and other essays. Why not check it out?

Three. I have another blog, Sibilant Fricative, where I post reviews of books and films science fictional. Most recently I reviewed the new Star Trek TV show Strange New Worlds.

Those are the main ones. I do have other blogs! (I sound like Groucho Marx: these are my blogs; if you don't like them I have others). So, and though I haven't posted there for a couple of months, I run a blog dedicated to Coleridge, upon whom I am presently undertaking some academic work. I do love Coleridge! The fact is, I find blogging a useful praxis when it comes to writing critical work: I blogged my way through H G Wells prior to writing my biography of him, and likewise read-and-blogged the whole of Anthony Burgess before writing my Burgessian novel The Black Prince (Unbound 2018). Those last two are no longer live blogs, in the sense that I no longer post material to them (any more than I do to this lockdown project blog); though Sibilant Fricative and my Notebook still get pretty regular updates of material.

So them's my blogs.

What else? Well, at the top of the post you can see me clutching my old CD of Blood and Chocolate. That's because I recently appeared on Stu Arrowsmith's excellent Dangerous Amusements podcast talking about my love of Elvis Costello, and you can hear what I had to say here. More news as we have it!

One more thing: buy my book.

Donna Scott reviews “The This” in PARSEC

The most recent issue of the excellent ParSec magazine (you can, and should, subscribe over at the NewCon website) includes a review of The This by the estimable Donna Scott. A snippet therefrom:

One of the things you may already have read about Adam Roberts’ latest science-fiction novel is that it is “Hegelian” – absolutely steeped in clever philosophical arguments after the school of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel – and concluded that you should have studied philosophy in order to ‘get’ it. Fear not! I myself came to this book knowing nothing and, having read it, I realise that far from knowing nothing, I now know everything, and what’s more I already knew it. Brilliant!

....That there are these overtly philosophical aspects to the novel might make it sound as though the book is a bit too clever to be readable, let alone enjoyable as a work of fiction, but this is not the case at all. Everything Roberts stuffs into this book has a lightness of touch that makes you wonder how he did it. Is he a magician? The power of his craft is to write a highly unusual story quite unlike anything else you have ever read, but which sweeps you along with an intriguing plot, sympathetic characters, and a theme that is not only terrifying, but also staggeringly plausible, rooted in the now of social alienation and pervasiveness of social media. Many others who have read this book are as enthusiastic about it as I am. You should join us! It is not a cult.The This, a science fiction novel, is available from all good, and some not so good, booksellers.

Sunday 26 June 2022

Monday 14 March 2022

Interview, and some "The This" reactions

First, here's a link to the long and (I think) interesting Phil Christman conducted with me for his substack. Phil is a good guy, and a really good writer, although, whilst I can't contradict his opening sentence here, I'm not sure it's the entire veritude. But you should definitely read the interview!

Second, in The This news: there have been some reviews, for instance here at SF Crowsnest, and New Scientist picked it as one of the SF books to look forward to in 2022. Over on Amazon there are (presently) 59 customer reviews, 59% of which are 5-star and 82% of which are either 5- or 4-star, which is pretty good going I think. Still, it's not a novel for everyone (click to embiggen):

On the other hand, Jessie Lethaby at the Times chooses The This as one of the best SF titles of 2022 so far, which is very good.

For myself, I only note that the official release date of the novel was exactly one hundred years, to the day, after the publication of Ulysses. I have decided to treat this fact as tremendously auspicious.

Wednesday 2 March 2022

"Purgatory Mount" on BSFA shortlist

Amazed and delighted that Purgatory Mount has made the 2022 BSFA Best Novel shortlist, especially considering how very strong the list is as a whole:

A Desolation Called Peace by Arkady Martine, TorThe winner will be announced Easter weekend, at Reclamation, this year's Eastercon.

Blackthorn Winter by Liz Williams, NewCon Press

Purgatory Mount by Adam Roberts, Gollancz

Shards of Earth by Adrian Tchaikovsky, Tor

Skyward Inn by Aliya Whiteley, Solaris

Green Man’s Challenge by Juliet E. McKenna, Wizard’s Tower Press

Tuesday 22 February 2022

This is the The This theme things

Some reactions to The This: Brian Cregg admires, but does not love, the novel. A more expansive (though of course not necessarily more accurate) response to the novel from Alan Jacobs, here. Goodreads is currently running at 4.5 out of 5, Buzzmag seems to like the book (or have I misunderstood?) and there are various other online responses, amazon reviews and so on.

And here is the estimable Phil Christman, praising with reservations The This (and talking a little about my other books too).

Roberts’s more recent books have taken an apocalyptic turn. He wrote a nonfiction study of apocalyptic media that just came out in November ... last year’s Purgatory Mount was apocalyptic, too—an attempt to guess where this will all end. Both it and The This gave me actual nightmares. (They also have one obvious technical flaw: his American characters sound a little too British. Something about the rhythm is off. It’s not that we never end sentences with an interrogative “, yeah?”, but we don’t do it very often, IME.) ... Roberts is kind of an anomaly: He is so smart, interesting, and productive that remembering he exists in this aggressively stupid mediascape always gives my mood a lift, but his books are so vivid in their depictions of suffering that I always get a little depressed when I read them. He’s not, I want to stress, a “grimdark” science fiction writer: his work is as powerful as it is because he sympathizes very much with people who are weak, imperfect, limited, and well-meaning, and he hates to see them lose everything, as, in this world, they inevitably do. Grimdark writers revel in reminding you that this is the case; they scorn you for ever forgetting it.Sorry for the nightmares, Phil: that's unconscionable of me.

Saturday 12 February 2022

Guardian on THE THIS

Today, The This reviewed in the Guardian. It's the second of my novels Lisa Tuttle has reviewed, and the first she has liked, so that's good.

Imagine a social media app implanted in the roof of the mouth for more immersive connectivity. This one small step turns out to be a giant leap in human evolution, a sort of telepathy that brings everyone together as parts of one vast, gestalt consciousness. But is that really such a great idea? Roberts takes a classic trope of speculative fiction, combines it with current preoccupations and views the whole in the context of religious belief and Hegelian philosophy. The result is dazzlingly inventive, exciting, funny and addictively readable.

Tuesday 8 February 2022

What does "The Times" (of London) think of THE THIS?

Book of the month

The This by Adam Roberts

The This is a new social media app. One that is injected straight into the body, so you can connect with other people without using technology. Its mass adoption leads humanity ineluctably to the creation of a hive mind-like collective. The story of the consequences of its spread is told through the eyes of various characters living at different epochs: Rich, the deskilled journalist; Adan, the phone-obsessed first-adopter; Ewe, the quantum bomb maker.Knees! Knees, I tell you! Down you go.

That this will be anything but a straight story is obvious from the first few pages as our nameless first protagonist is reincarnated through every single human life, past, present and future, and becomes in the process some sort of Übermensch. And this is no mere flourish: at the heart of the British writer Adam Roberts’s dizzying conflagration of ideas sits an unlikely theological treatise titled The Odourless God, which turns out to explain precisely and convincingly, in quasi-anthropological terms, why pointless social media spats happen, why they are addictive and why they will transform us, sooner than we think, into some ghastly amorphous galactic entity.

Roberts, sci-fi’s most outrageous experimentalist, has for quite a while been trying to renew the toehold that religious thought once had on the genre. In The This he has succeeded, with arguments that will bring modern readers (if they have any sense) to their knees in terror.

Monday 7 February 2022

Wednesday 26 January 2022

"The This": reviewed in SFX

The novel itself is published Feb 3rd, but reviews are already coming in. Click to embiggen. Five stars! Can't complain.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)